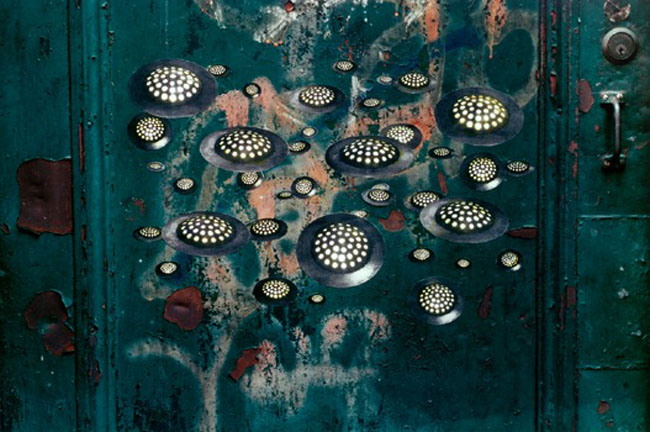

Images from Dan Witz.

How did you get started in the street art scene?

I got started doing street art in the late 1970’s as an art student in downtown New York City. Back then, the idea was that if the world was a fucked up place that desperately needed changing, and contemporary art (and art schooling) had miserably failed us in this respect, then it became our job as artists to not only challenge the system but also change it. Much as I enjoyed museums and galleries, they were part of the problem: clearly exhibiting paintings on some white wall somewhere wasn’t going to change many minds. So, in search of more immediate impact, most of my friends started bands, and I did that for a while too, but I was a painter at heart. Inspired by the awesomely graffiti subway trains, I started going out tagging (or my version of it).

When describing your work, what would you say are the main themes?

If there was a consistent theme running through the past 35 years it would be a wish to stop people in their tracks and make them go, “WHAT THE FUCK?!!?”. My style is suggested somewhat by theme (content), but more so by my need to avoid getting caught and arrested. For my first real street project, in 1979, I painted tiny realistic hummingbirds. Each one took about 2 hours to paint. New York City was such a chaotic mess back then that if I was quiet and kind of hunched over and folded my shoulders in, I could paint in public without anyone paying too much attention. In the 80’s and 90’s I made complicated multi-image sticker installations, each with it’s own intricate airbrush shadow painted on the wall. Installation was a complicated choreographed maneuver and could take up to a half an hour. I could get away with this if I worked in marginal (low income) neighborhoods and was mindful of what walls I chose. But, starting in the late nineties, with the zero police tolerance in NYC brought on by gentrification, I absolutely could not be seen in the act so my style was forced to adapt. The pieces I do now are made in the studio and installed on site, usually in under a minute. This need for speed has forced me to develop new techniques and – and I love the irony here – these technical innovations have given me the means to do much more street art than if the authorities had left me well enough alone.

What are your favourite materials to work with?

It’s a mix. I’ll use anything. My goal is to make it seem as if a real person (or whatever) is there. These days I start with digital media then paint over it using all the tricks of illusionistic painting I know. Mostly it’s glazing and contours and colour technique but I’ve really come to love the airbrush. No street piece of mine is done until I’ve touched it up a bit with the airbrush. Honestly, I’m not really sure why this works so well, but it’s super gratifying when I step back after airbrushing and everything snaps into 3-D.

What has been your most challenging and/or rewarding piece of work thus far?

The summer of 2012’s Amnesty International collaboration in Frankfurt called Wailing Walls. That was the biggest, coolest thing I’ve ever done. Also, in 2010, Gingko Press published a monograph on my work, Dan Witz: In Plain View. 30 Years of Artworks, Illegal and Otherwise. Usually I’m not so pleased with published stuff about me, but I was very proud of this.

How do you go about creating your street art? How do you choose a street/environment?

Usually my ideas stem from a reaction to the last thing I did. With new pieces I try and amend the failures and shortcomings of the preceding project. Every time I begin a series, I don’t consider it successful until my previous year’s work looks obsolete to me. This can be challenging at times, but for once my chronically restless and dissatisfied personality turns out to be useful – my work keeps evolving and stays fresh and I’m usually pretty psyched to wake up in the morning and get to work.

As far as choosing where I put my stuff, that depends on several factors. First, my subject matter, where it’ll have the most resonance etc. Then the actual object and how it needs to be installed, and, as important as anything, is location: the pieces should be where the most people can see them – but where they won’t be too vulnerable, or where I won’t get caught putting them up. This last part involves a complicated calculus that is actually as creative a part of the process as anything else.

You’ve been creating street art since 1979. How has your work and the idea around street art changed since then?

When I started out I began using a simple message in a bottle approach to making street art. Location and placement were mostly random: the main idea was that free anonymous art with no promotional agenda existed. In the early 2000’s when street art started getting popular, this strategy got to be increasingly difficult, so I began conceiving and planning my work differently. Rather than competing for attention on the public commons, I tried to make my installations so subtle and so integrated into the urban environment that they were practically invisible. Nothing was more satisfying to me than having hundreds of people somnambulate by my very obvious faux grates every day and not see them. Part of this came from my punk-rock background, my bite-the-hand-that-feeds-me need to twit the bourgeois-zee, but also this was my way of responding to all the brilliant new artists redefining what it meant to be working on the street.

All along street art has never been a means to get ahead for me. I still believe in anonymous, not-for-sale art as a meaningful response to art-world art – a genuine game changer. And I still enjoy doing it, everything about it, especially penetrating into places that conventional art making can’t.

Have you ever been arrested?

No. Or I should knock on wood and say, not yet. The law of averages gets me stopped by the cops every now and then, but thankfully they’ve never taken me in. I’m waiting for the day when they’re sitting in their car checking my license and one of them decides to Google me. You’ll definitely be getting those annoying legal-fee fund raising e-mails from me then.

What attracted you to the streets of London?

Mostly that I was brought here by Lazarides Gallery, and before that by StolenSpace. But I’ve always enjoyed working in London. These days, next to NYC it’s my favorite city to do street art in (or on, or to.) For one thing, the light in both places is very similar, which really suits the emotional temperature of my work. Also, when you get up close in London there’s a grit in the pores that’s a lot like New York’s. Since I’m usually transplanting a NYC grate, my pieces feel at home.

Why do you have such an interest in prisoners?

With these pieces the disenfranchised characters and grate imagery made perfect sense – they were a logical expansion on the previous years’ projects. As I began working though, I sensed a connection to a larger theme, I just had to do my daily easel-sit and paint my way there. Usually this blind alley way of going about my business would have been fine, I’m in no hurry and I’m not really one of those artists who is known for one kind of work and has expectations to fulfill. But for these pieces I was employing models, and we needed a story to work with. Also, with my production process being so complicated and time consuming (and expensive now) months of fumbling around has become impractical.

So while in the midst of this gestation phase, Amnesty International contacted me to collaborate on their 2012 campaign in Frankfurt. It was a perfect match. I’d already been painting prisoners, but the hook was that now these would literally be prisoners. More than symbols, these were real people with names and case histories.

I mentioned earlier that this was the coolest thing I’ve ever done. The best synergy ever, probably because it was about more than me, or art.

Why choose to transform phone boxes (in London).

Yeah, I was worried about this. I mean this had the potential to be corny or wrong footed, but honestly I just love that red so much I couldn’t help myself. And the prisoner imagery always seems to trump my reservations. Also the phone booths fit my code for defacement – in that they’re not really necessary anymore and so ubiquitous and taken for granted that they’re almost invisible. I’m pretty satisfied with this piece. Maybe because it was so difficult and challenging, what with the winter weather, the cameras, the weird traffic warden spy-guys, and the fact that those things are built like WWI battleships and are impossible to drill into. It wasn’t until my third try that I finally got the piece up, and as usual with me, overcoming obstacles and hardships makes the result a lot more gratifying. I should thank that traffic warden dude for chasing me off the first time. I would never have had the guts to put this one where I did if I wasn’t cold and wet and totally fed up.

What do you do when you’re not creating art?

We have a 16-month-old kid.

How has your style developed through out the years? Have you always preferred to paint in a super-realistic style?

Yeah, I’ve never felt a need to express myself in any other way. On one level all my work over the years has been about exploring what realist painting can do that no other visual media else can – what’s intrinsically unique about this way of painting. In the past I’ve used my representational skills to create the illusion of light and space and movement, which I’m still into, but these days it’s mostly about The Presence – that moment when you’re there, and you suspend disbelief and surrender yourself to the universe of the painting. This is what has always excited me about looking at art – that crazy moment when you leave your body and go down the artist’s rabbit hole to places unknown.

What are people’s reactions to your work? Have you ever had bad reactions?

Of course, doing street art is by nature an act of cultural aggression. That said; I understand that I’m working on the public commons and try my best to use discretion. But that said I’m still a punk. The most game changing part about the punk movement was that they didn’t care what anyone thought about them; they didn’t give a fuck about pleasing anyone and (sometimes, actively) even wanted you to dislike them. At the time this was a revelation to me, and really freed me from a lot of craven ambitions and hang-ups. So if everyone was happy about my work I’d be worried about it.

I think I mentioned this earlier but last year when I was using some pretty dark imagery I tried to make it so integrated into the environment that 99% of the people passing by wouldn’t even notice it. This was a lot more fun than it sounds. No one ever saw my pieces. And they were right out there in plain view. Watching everyone walk by oblivious to a naked chained prisoner two feet away from their faces was one of the most perversely satisfying experiences I’ve ever had doing street art.

Has the stigma attached to street art ever put you off?

Depends what stigma you’re referring to. Back in the 80’s and 90’s before many people were doing street art, the art world tended to look down on people like me. There was a general feeling that this was outsider’s art, and trained artists did it because they wanted attention and couldn’t get shown in ‘real’ galleries. There was even an insinuation that maybe we were even a little crazy (and not in a fun way). But I’ve gotten used to being condescended to by arts professionals. In fact, whenever some smug curator type in silly eyeglasses gives me that armored “I’ve never heard of you” look, I get this private little puff of glee inside of me. I can’t help it; it’s like getting a secret glimpse of some endangered species – the emperor with no clothes. Although, I’d be dishonest if I didn’t admit that sometimes it crossed my mind that they might be right about me being crazy.

These days, doing street art has become such a hipster cliché that I suppose I should be embarrassed that I still do it. I’m not. Basically I’m too lazy to worry about hipster clichés.

What is your main reason for making art?

Do I have a main consistent reason for making art? I’m not sure. If I do it’s nothing too profound. Probably it’s something prosaic like, “it’s what I do best”, or “it’s all that I’m capable of anymore”. Over the years most things non-art related in my brain have atrophied away. Seriously, it’s cobwebs in here. Dirty diapers and dried up old palettes, that‘s all I got.

Is there anything that you dislike about the street art scene?

No. But I’m pretty insulated from the crass commercial side of the scene. And for the most part the artists I meet don’t seem to be threatened by me. Probably because I’m old. And I’ve never hit the money which seems to be when the friction and trash-talking starts. The truth is, my new work takes so much time and energy that I don’t have much attention span left over to worry about career politics or much else. And that crazy kid keeps me pretty busy too.

Thanks Dan.

Street Art London

DanWitz.com

Hello, we keep taking street art photos of London since two years and we really like to discover every day a new one. This is a newcomer if you didn’t see yet:

http://acatfromlondon.wordpress.com/2013/03/31/new-street-art-in-ada-street/

Cheers

WOW! I love dan witz’s work a lot. 😀

Innovation and creativity at its best. Absolutely stunning visual symbolism, these type of paint techniques can’t get any better.